An Earth-sized planet 40 light years away has emerged as a target in the international search for extraterrestrial habitable worlds and evidence of life.

Scientists using data from the largest telescope in space said Trappist-1e could have liquid water and an atmosphere rich in gases such as nitrogen, which makes up more than three-quarters of the Earth’s air.

Powerful new means of astronomical observation and analysis have boosted the quest to unlock the secrets of so-called exoplanets such as Trappist-1e, which are outside our solar system.

“We finally have the telescope and tools to search for habitable conditions in other star systems, which makes today one of the most exciting times for astronomy,” said Ryan MacDonald, a co-author of the research published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters journal on Monday. “Trappist-1e has long been considered one of the best habitable zone planets to search for an atmosphere.”

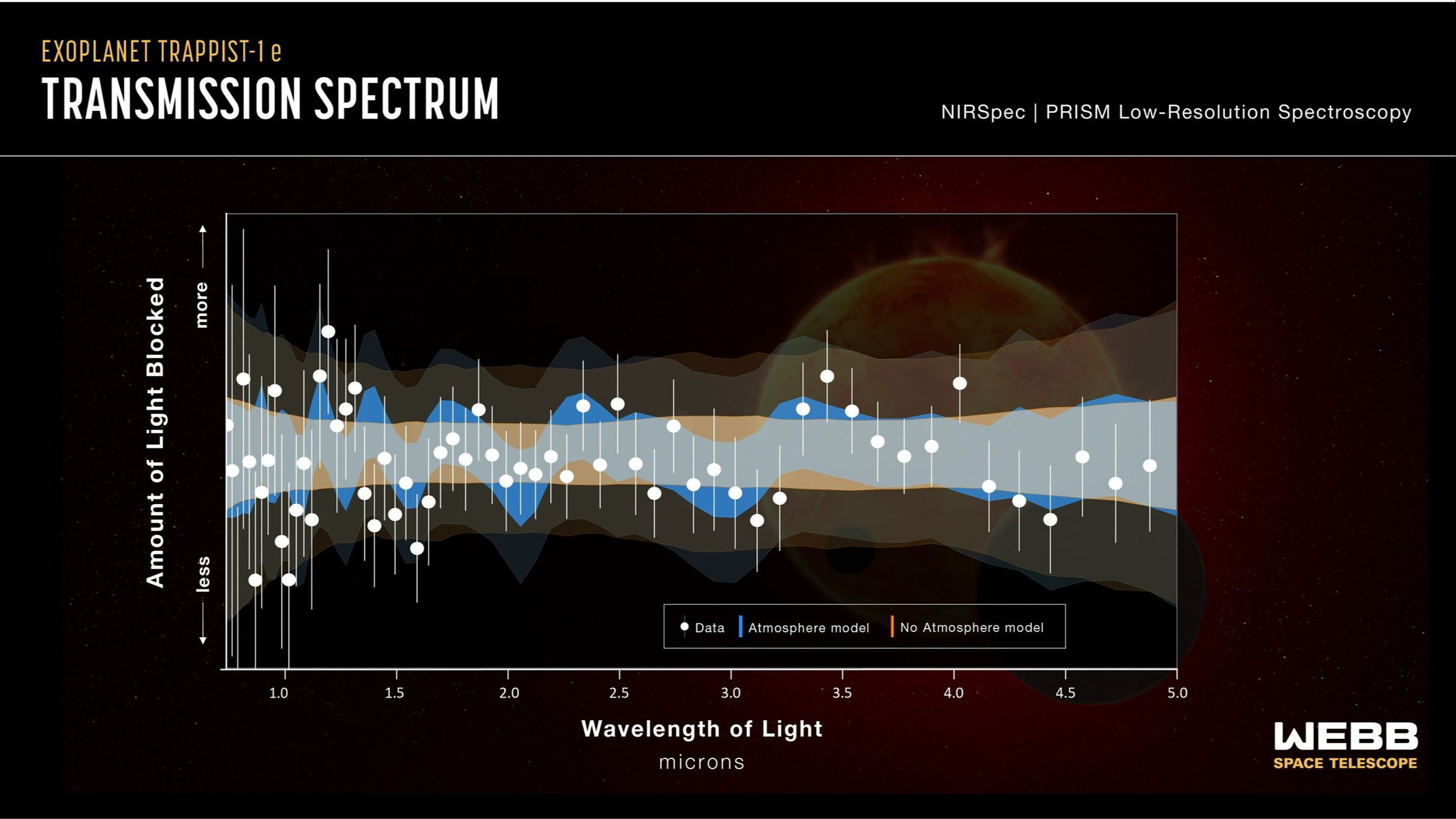

The scientists harnessed structural data on Trappist-1e from the James Webb Space Telescope, which was launched in 2021 to probe the history of the universe. The cosmic observatory can measure how the composition of light from Trappist-1e’s star changes after passing through the region where the planet’s atmosphere would be. The researchers spent more than a year correcting readings to account for the distorting effects of magnetic fields on the star’s surface.

They concluded that Trappist-1e could have an atmosphere that would allow the existence of surface water in the form of a global ocean or icy expanse. Such an atmosphere might contain gases such as nitrogen, which plays a crucial role in sustaining ecosystems on Earth.

The researchers could not yet rule out that Trappist-1e was “a bare rock with no atmosphere,” warned MacDonald, a lecturer in extrasolar planets at the University of St Andrews. They hope to use further data gathered by the Webb telescope over the coming years as it continues to orbit the sun.

The discovery of thousands of exoplanets has widened the hunt for habitable worlds. Some planets, such as Jupiter and Saturn, are “gas giants” with no rocky surface or atmosphere to make them amenable to Earth’s carbon-based lifeforms.

The unveiling of an international project in April pointing to what its authors claimed as the strongest evidence yet of extraterrestrial life has sparked intense debate. The scientists said they had found molecules suggesting the possible activity of living organisms in the atmosphere of the planet K2-18b, 124 light years from Earth.

K2-18b is a so-called Hycean world: a world covered in liquid water with a hydrogen-rich atmosphere at habitable temperatures. The scientists stopped short of claiming they had found definitive proof of life, while some others in the field stressed the possibility of alternative explanations for the data.

The Trappist-1e research was “incredibly significant” in its approach to analysing possible atmospheres of rocky exoplanets orbiting active stars, said Paul Rimmer, an astrochemist at Cambridge university. If it were found to be habitable, the next stage would be to search for signature chemicals in the atmosphere indicating life, he added, although this would not be straightforward.

“We have poor data for exoplanets and we can’t really go there any time soon to check if there’s life,” he said. This meant it might only be possible to attribute the candidate chemical signatures to a group of planets, rather than knowing with high confidence about the presence of life on any individual one, he said.